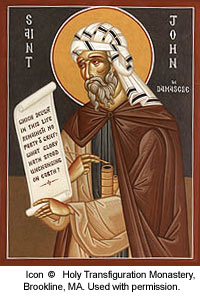

St. John Damascene

St. John Damascene has the double honor of being the last but one of the fathers of the Eastern Church, and the greatest of her poets. It is surprising, however, how little that is authentic is known of his life. The account of him by John of Jerusalem, written some two hundred years after his death, contains an admixture of legendary matter, and it is not easy to say where truth ends and fiction begins.

The ancestors of John, according to his biographer, when Damascus fell into the hands of the Arabs, had alone remained faithful to Christianity. They commanded the respect of the conqueror, and were employed in judicial offices of trust and dignity, to administer, no doubt, the Christian law to the Christian subjects of the Sultan. His father, besides this honorable rank, had amassed great wealth; all this he devoted to the redemption of Christian slaves on whom he bestowed their freedom. John was the reward of these pious actions. John was baptized immediately on his birth, probably by Peter II, bishop of Damascus, afterwards a sufferer for the Faith. The father was anxious to keep his son aloof from the savage habits of was and piracy, to which the youths of Damascus were addicted, and to devote him to the pursuit of knowledge. The Saracen pirates of the seashore neighboring to Damascus, swept the Mediterranean, and brought in Christian captives from all quarters. A monk named Cosmas had the misfortune to fall into the hands of these freebooters. He was set apart for death, when his executioners, Christian slaves no doubt, fell at his feet and entreated his intercession with the Redeemer. The Saracens enquired of Cosmas who he was. He replied that he had not the dignity of a priest; he was a simple monk, and burst into tears. The father of John was standing by, and expressed his surprise at this exhibition of timidity. Cosmas answered, "It is not for the loss of my life, but of my learning, that I weep." Then he recounted his attainments, and the father of John, thinking he would make a valuable tutor for his son, begged or bought his life of the Saracen governor; gave him his freedom, and placed his son under his tuition. The pupil in time exhausted all the acquirements of his teacher. The monk then obtained his dismissal, and retired to the monastery of S. Sabas, where he would have closed his days in peace, had he not been compelled to take on himself the bishopric of Majuma, the port of Gaza.

The attainments of the young John of Damascus commanded the veneration of the Saracens; he was compelled reluctantly to accept an office of higher trust and dignity than that held by his father. As the Iconoclastic controversy became more violent, John od Damascus entered the field against the Emperor of the East, and wrote the first of his three treatises on the Veneration due to Images. This was probably composed immediately after the decree of Leo the Isaurian against images, in 730.

Before he wrote the second, he was apparently ordained priest, for he speaks as one having authority and commission. The third treatise is a recapitulation of the arguments used in the other two. These three treatises were disseminated with the utmost activity throughout Christianity.

The biographer of John relates a story which is disproved not only by its exceeding improbability, but also by being opposed to the chronology of his history. It is one of those legends of which the East is so fertile, and cannot be traced, even in allusion, to any document earlier than the biography written two hundred years later. Leo the Isaurian, having obtained, through his emissaries, one of John's circular epistles in his own handwriting -- so runs the tale -- caused a letter to be forged, containing a proposal from John of Damascus to betray his native city to the Christians. The emperor, with specious magnanimity, sent this letter to the Sultan. The indignant Mahommedan ordered the guilty hand of John to be cut off. John entreated that the hand might be restored to him, knelt before the image of the Virgin, prayed, fell asleep, and woke with his hand as before. John, convinced by this miracle, that he was under the special protection of our Lady, resolved to devote himself wholly to a life of prayer and praise, and retired to the monastery of Saint Sabas.

That the Sultan should have contented himself with cutting off the hand of one of his magistrates for an act of high treason is in itself improbable, but it is rendered more improbable by the fact that it has been proved by Father Lequien, the learned editor of his works, that St. John Damascene was already a monk at Saint Sabas before the breaking out of the Iconoclastic dispute.

In 743, the Khalif Ahlid II persecuted the Christians. He cut off the tongue of Peter, metropolitan of Damascus, and banished him to Arabia Felix. Peter, bishop of Majuma, suffered decapitation at the same time, and St. John of Damascus wrote an eulogium on his memory. Another legend is as follows: it is probably not as apocryphal as that of the severed hand: -- The abbot sent St. John in the meanest and most beggarly attire to sell baskets in the marketplace of Damascus, where he had been accustomed to appear in the dignity of office, and to vend his poor ware at exorbitant prices. Nor did the harshness of the abbot end there. A man had lost his brother, and broken-hearted at his bereaval, besought St. John to compose him a sweet hymm that might be sung at this brother's funeral, and which at the same time would soothe his own sorrow. John asked leave of the abbot, and was curtly refused permission. But when he saw the distress of the mourner he yielded, and sang him a beautiful lament. The abbot was passing at the time, and heard the voice of his disciple raised in song. Highly incensed, he expelled him from the monastery, and only re- admitted him on condition of his daily cleaning the filth from all the cells of his brethren. An opportune vision rebuked the abbot for thus wasting the splendid talents of his inmate. John was allowed to devote himself to religious poetry, which became the heritage of the Eastern Church, and to theological arguments in defense of the doctrines of the Church, and refutation of all heresies. His three great hymns or "canons," are those on Easter, the Ascension, and Satin Thomas's Sunday. Probably also many of the Idiomela an Stichera which are scattered about the office- books under the title of "John" and "John the Hermit" are his. His eloquent defense of images has deservedly procured him the title of "The Doctor of Christian Art."

The date of his death cannot be fixed with any certainty; but it lies between 754 and before 787.